In ancient Rome, members of the social elite would often appoint an anteambulo—which translates to “one who clears the path.” An anteambulo was typically a writer or performer who was talented but lacked resources to move upward—they were First Century starving artists.

This anteambulo would literally walk in front of his patron, clearing both the metaphorical and physical paths: communicating messages, finding opportunities, eliminating inefficiencies, and making the patron’s life easier. In exchange, the anteambulo would receive food, housing, protection, and—if he played his cards right—a career.

Aside from being born into the upper crust of society, becoming an anteambulo was arguably the most efficient way to ascend the social hierarchy. You traded favors for favors. The person who cleared the path could ultimately determine his own destination.

Fast forward 2,000 years and the concept of an anteambulo is, tragically, little more than a relic of ancient history. But the underlying principle may be the most valuable piece of career advice out there. It allows you to eschew traditional hiring processes and essentially hack the system.

Let me explain.

After finishing an internship with a marketing agency during my senior year in college, I told my boss I wanted to parlay my gig into a full-time career. There was only one problem: They weren’t hiring. I was tempted to start cold calling random agencies who were actively seeking entry-level employees, but I had recently read about the anteambulo concept in Ryan Holiday’s Ego Is the Enemy and decided to give it a shot.

What could I do to make these guys’ lives easier?

How could I turn this into a favor for them instead of a favor for me?

What could I bring to the table to make their agency better?

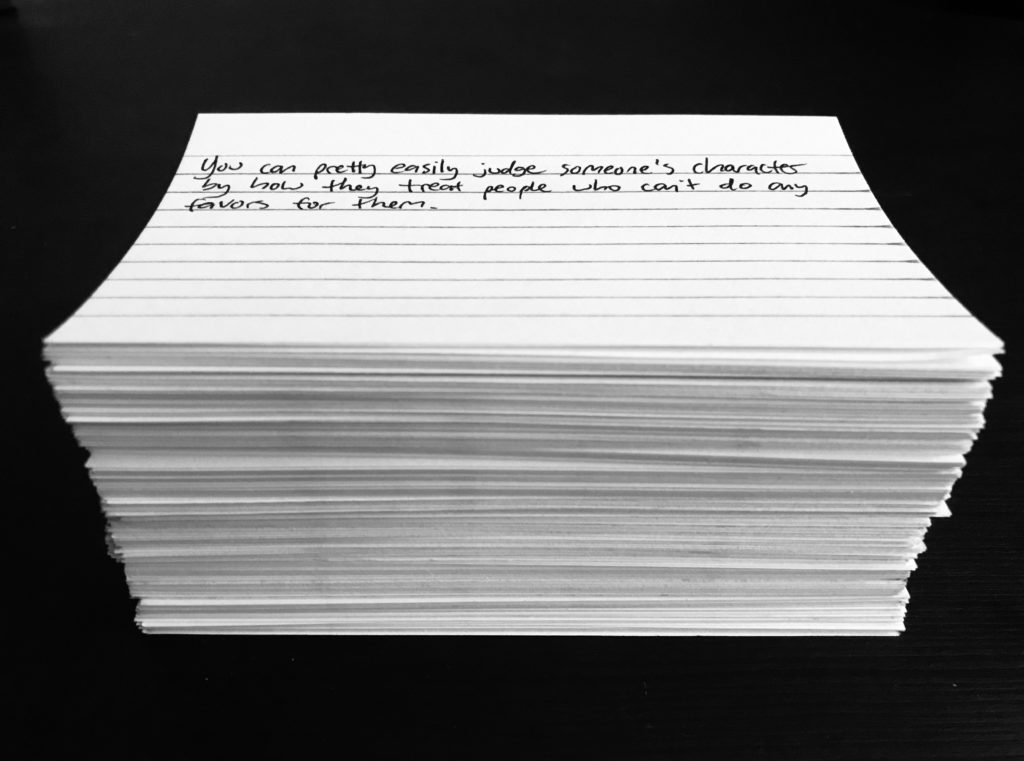

With those questions in mind, I typed a (lengthy) “reverse offer letter” to the senior partners outlining what I wanted to do for them:

I will write a book with you.

I will manage the agency’s blog and newsletter.

I have fresh creative ideas that I want to share with your clients.

And much more.

I didn’t request a salary nor a title—I just wanted to work. After a few email exchanges, I had a job offer and started the following month. Holiday was right: If you make yourself useful enough, it doesn’t matter who’s hiring.

15 months later, I needed a change of pace. Through a chance encounter, I met a VP from NoCoast Originals and mentioned I was open to new opportunities. She thought I’d mesh well the team, but of course, they didn’t have any open positions.

I tried the same strategy, but this time the wheels got stuck in the mud. After two reverse offer letters and four meetings, nothing had transpired. So instead of bringing ideas to the table, I brought something better: a client.

Through that VP, I met a public figure who wanted to write a book, but didn’t have the time nor the writing chops to go at it alone. I told him I’d love to collaborate with him to write it and brought the idea to the partners at NoCoast. I explained that the project could open new doors for their agency, and most importantly, pay for my salary.

Done.

I’m not saying this process is an exact science. It might not work in every industry. But what do you have to lose by hustling? The worst case scenario is being ghosted via email; the best case is a new job. Everyone is waiting to be swept off their feet—they just don’t know it.

A few additional notes on this anteambulo stuff:

1. The best jobs aren’t on Indeed or LinkedIn. You’ll be happier if you carve out your own niche, especially if you like to create stuff.

2. If you have to wait for an assignment to be given to you, you’re doing something wrong.

3. Your job is to make your boss’s life easier, not make your own life harder.

4. It’s not about optics (working long hours, playing martyr)—it’s about efficiency and execution.

5. Don’t expect to take credit for your work. In fact, letting important people take credit for your ideas is half the battle.

Oh, and most importantly, don’t expect any of this to happen overnight. So, stay on the radar, but don’t be a creep. Send an interesting email every couple of weeks. Ask smart questions. Work for free.

Remember, “Create a job that doesn’t exist for someone we don’t know” is about as close to the bottom of a busy person’s to-do list as you can get. Act accordingly.

Have you read these five books to base your life on? Get the list, plus seven strategies I stole from legendary marketers to promote your work.

I do not know what Victor Ramirez did to warrant solitary confinement. Frankly, I do not care. When I decided to participate in

I do not know what Victor Ramirez did to warrant solitary confinement. Frankly, I do not care. When I decided to participate in

Whether you think Goldman Sachs is a bastion of evil or doing “God’s work” is irrelevant. Take a step back and consider the situation: this chairman had pockets deeper than the Grand Canyon and a rolodex of the world’s power elite in his pocket. Why would he waste his time with some eager beaver with a mysterious agenda?

Whether you think Goldman Sachs is a bastion of evil or doing “God’s work” is irrelevant. Take a step back and consider the situation: this chairman had pockets deeper than the Grand Canyon and a rolodex of the world’s power elite in his pocket. Why would he waste his time with some eager beaver with a mysterious agenda?