Like to read? Make sure you get the list of 5 books to base your life on, plus 11 writing lessons from iconic authors. Just let me know where to send them. Enjoy!

It has never been easier to produce creative work than it is today. SoundCloud, Instagram, blogs, and the internet in general have nullified the gatekeepers who once decided who was “allowed” to have an audience. The probability of bringing an idea to fruition in 2018 is higher than anybody could have dreamed 100, 50, or even 10 years ago.

And yet, thousands of people still haven’t gotten with the program.

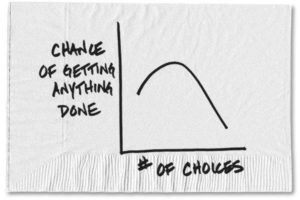

We hear the phrases “I want to” or “I’m going to” ad nauseam: about the clothing line, about the album, about the startup, about the book — all to no avail. It’s as if the sheer volume of opportunities paralyzes us from following through with any of them.

I met up with Kevin Thomas (a friend of mind who also writes) to shed some light on this issue and hopefully encourage others to stop talking and start doing if they have that creative itch.

Here’s our conversation:

D: I’ve always been intrigued by this quote from Austin Kleon: he says “too many people want to be the noun without doing the verb.” They want to be an entrepreneur, but they shy away from doing the necessary work to earn that title. They don’t want to write, they want to have written. I think that has a lot to do with the nature of media right now. We’re surrounded by pictures, videos, and stories about people doing all of these amazing things, and we assume we have to do the same — even if there’s no real purpose behind it.

K: I agree entirely. But it goes beyond that to the point of whether or not a person feels like they have to write. Personally, I write because I need to, it feels like the only way that I can continue my own existence. It takes a ton of reflection to reach the point where you realize that you have to write, that you need to write to continue, for your own survival.

D: Once you do find that purpose, though, it’s so easy to get caught up running your mouth about it that you forget you actually haven’t done shit. I remember binge-reading Ryan Holiday’s articles during my first two years of college and thinking how cool it would be to write my own stuff. Psychologists call it ‘narcotizing dysfunction’: you confuse your thoughts with actions. I think the only way to combat this is to take the initiative, do the work, and realize you’re probably going to suck for at least a year.

K: Yeah, after you keep writing and writing because you have to do it, once you’re stuck in the work and trapped by this sense that your work isn’t good enough because you know what is good and isn’t, you have to move onto the next step and actually share your work. Spoiler alert: you’re never going to be satisfied with your work. Everyone that I’ve met that creates anything is hypercritical of their own creation, but it’s not about being satisfied with your work, it’s just about being not-unsatisfied, accepting that, while it isn’t perfect, you gotta get it out there into the hands of others.

D: It all ties back to the introduction: there’s nobody telling you what you can or can’t create. You don’t need permission. You don’t need an MFA to write and you don’t need a record label to make music. I worked with a music producer who made his first beat in his dorm room with a bong. The song went viral and he just landed a gig to perform at a music festival. Bottom line: if you want to be a writer, write. If you want to be a musician, make music.

K: As we talked about earlier, it’s about writing not for the sake of having written, but because you feel like you need to write because you have to get something out. Some of the greatest writers, in my opinion, have no formal education in how to write. Etheridge Knight is one of those people. He started writing poetry while in prison, and his work is insanely good. You need to just start writing, and follow it up by reading and then thinking about why it’s good. You don’t need a degree to tell you why you dig something, you just need to sit back and think about why you dig it, and incorporate that into your own stuff. But, you gotta have stuff to incorporate it in.

D: One of the biggest excuses for not following through is time. Everyone says they’re too busy, which is funny because the evidence suggests that’s not the case at all. There always seems to be time for Fortnite, liking shit on Instagram, or sleeping until 9 or 10. If you can make time for those things but not your “passion,” chances are that wasn’t your passion in the first place and you should reevaluate.

K: This pisses me off. You really need to ask yourself how badly you want it, and whether or not you want it at all. It’s about finding out your own values, and sticking to them. Holding yourself accountable to doing, instead of just thinking about it, or wanting to do it. If you need to write for your own survival, if you’ve reached that point, then you have to do it. Plain and simple. Set a routine for writing, don’t set a routine for having written. Don’t say, oh, I’ll write 500 words every single day and I’m good. Say, I’ll work on something for an hour a day and that’s it. If you’re writing because you need to write, because you have something to say, you might write 3,000 words that day. Or maybe you’ll write 100 because some days are hard. But you can’t let yourself be stopped because you get lost in the final idea, thinking about how you’re gonna be famous, how cool having written a book will be, or whether or not you can survive off your writing (meaning money) instead of because you’re writing.

D: The topic of money reminds me of another important point. It seems counterintuitive, but giving your work away for free is arguably the best way to build a long-term relationship with an audience. Put yourself in their shoes: somebody (who you might not even know) is already asking you to spend their valuable time consuming what you created; and on top of that you’re also asking for their money? You need to make it as easy as possible for them to enjoy your work, and money is the biggest barrier to entry. I say get rid of it, especially early on.

K: This is something that I feel conflicted about. But, it goes back to what I just mentioned, are you creating because you want to survive off your writing, or are you writing to survive? Personally, I’m doing the latter. I have friends who are doing both, but I’m privileged enough to do only the latter. I’ve released two zines of poetry, one with doodles included, and I was able to give them away for free because I could print them at my university for free using my own printing money and other’s printing money. I gave them away for free because I wanted to make personal connections, and because I needed to say so many things that I didn’t feel like I could say except through poetry and doodles. So, again, you have to think about your values. What the hell do you want? To write or to have written? You and I have to write, and so we do.

I didn’t know who Anthony Bourdain was until the news of his tragic passing made it into headlines earlier this month. From what I understand, the man was a prolific worker, an impressive TV personality, and one of the world’s most influential chefs. But it wasn’t until I came across one of his quotes that I got a glimpse into Bourdain’s candid persona.

I didn’t know who Anthony Bourdain was until the news of his tragic passing made it into headlines earlier this month. From what I understand, the man was a prolific worker, an impressive TV personality, and one of the world’s most influential chefs. But it wasn’t until I came across one of his quotes that I got a glimpse into Bourdain’s candid persona.

A few weeks ago, I saw an infomercial for the Bacon Bonanza Copper Cooker: a contraption that lifts bacon away from grease during the cooking process to lower its fat content. For $19.95 (plus shipping and handling) I’m told I can revolutionize the way I eat bacon.

A few weeks ago, I saw an infomercial for the Bacon Bonanza Copper Cooker: a contraption that lifts bacon away from grease during the cooking process to lower its fat content. For $19.95 (plus shipping and handling) I’m told I can revolutionize the way I eat bacon. Of course, there’s a philosopher who was fascinated by such a bothersome question. His name was Rene Girard, a former professor at Stanford who passed away a few years ago. Girard’s studies in literature, history, and sociology led him to develop a pretty cynical theory for why we want things:

Of course, there’s a philosopher who was fascinated by such a bothersome question. His name was Rene Girard, a former professor at Stanford who passed away a few years ago. Girard’s studies in literature, history, and sociology led him to develop a pretty cynical theory for why we want things:

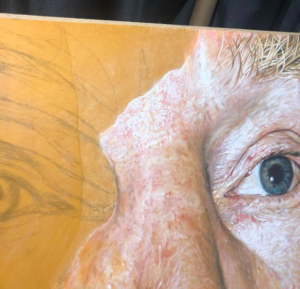

Rick is the co-founder of Hill Investment Group in St. Louis where I was working as a marketing intern at the time. At 75 years old, he doesn’t plan to retire any time soon. He oozes wisdom and has a contagious energy that people half his age do not.

Rick is the co-founder of Hill Investment Group in St. Louis where I was working as a marketing intern at the time. At 75 years old, he doesn’t plan to retire any time soon. He oozes wisdom and has a contagious energy that people half his age do not.

For millions of people, the solution is popping an Adderall or Vyvanse. I haven’t tried either – apparently it’s like having a cheat code to focus. But as with all cheat codes, you never learn how to master the game. And in this case, it’s the game of your career, your life.

For millions of people, the solution is popping an Adderall or Vyvanse. I haven’t tried either – apparently it’s like having a cheat code to focus. But as with all cheat codes, you never learn how to master the game. And in this case, it’s the game of your career, your life. Among the artifacts on display is a collection of women’s underwear branded with Washington Redskins, Chicago Blackhawks, and Cleveland Indians logos. This may, according to the exhibit’s description, cause unintended harm to viewers, but can provide windows that allow us to see more clearly how history influences today’s social issues.

Among the artifacts on display is a collection of women’s underwear branded with Washington Redskins, Chicago Blackhawks, and Cleveland Indians logos. This may, according to the exhibit’s description, cause unintended harm to viewers, but can provide windows that allow us to see more clearly how history influences today’s social issues.