Your life is center stage. You are being watched. Despite the other 7 billion people in the world, the spotlight is on you, putting your every failure, imperfection, and blemish on display for all of us to analyze. This is a tough belief to hold in your head every day.

But it’s completely bogus.

This belief that everyone is watching us or that our lives are the focal point of others was first observed by the psychologist David Elkind in 1967. He called it the ‘imaginary audience,’ and noticed that this tendency was common, even normal among adolescents. We all experience the phase of fearing the disapproval of our family, peers, or strangers, and Elkind believed it was necessary to outgrow this phase in order to become more grounded in reality. But today it seems that it’s not only awkward tweens, but adults who struggle to shed this unwarranted performance anxiety that’s supposed to reside as we mature.

The case can be made that social media has exaggerated the effects of our own imaginary audiences. Our Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter feeds certainly blur the line between our perception of what others think about us and what people actually think. But that’s beside the point. For thousands of years, we’ve been trying to figure out how we can care less about what others think of us, or for that matter remind ourselves that people rarely even think of us at all.

In the first century AD, the Greek slave-turned-philosopher Epictetus discussed the hypothetical case of a musician who feels no anxiety while he practices by himself; but when he goes on stage he succumbs to pressure and can’t perform, even though he has the most talent. “For what he wishes is not only to sing well,” says Epictetus, “but likewise to gain applause. But this is not in his own power.”

How often do act the same way? With every completed task we flail and grasp for approval and admiration. We place less value on the merits of our work than the applause that follows it. And if that applause doesn’t come, we pout, make an excuse, or blame someone else.

Schopenhauer proposed a question nearly 1,700 years after Epictetus died which I refer to often: “Would a musician feel flattered by the applause of his audience if it were known to him that it consisted entirely of deaf people?”

Your metaphorical “audience” today might as well be entirely deaf because 99.9 percent of people don’t care what you’re doing. Behind the likes and retweets is a desert of apathy and carelessness. They don’t care about your Snapchat story. They don’t care how your hair looks. They don’t care that you graduated or won a trophy. But we insist that the spotlight is shining brightly upon us in both good and bad times. We insist that the tribe really does care.

Steven Pressfield sums this up well in his book Turning Pro:

“The amateur dreads becoming who she really is because she fears that this new person will be judged by others as ‘different.’ The tribe will declare us ‘weird’ or ‘queer’ or ‘crazy.’ The tribe will reject us. Here’s the truth: the tribe doesn’t give a shit. There is no tribe. That gang or posse is, in fact, a conglomeration of individuals who are just as fucked up as we are and just as terrified.

Each individual is so caught up in his own bullshit that he doesn’t have two seconds to worry about yours or mine, or to reject or diminish us because of it. When we truly understand that the tribe doesn’t give a damn, we’re free. There is no tribe, and there never was. Our lives are entirely up to us.”

Dominic Vaiana studies writing and media strategy at Xavier University. You can get the PDF “11 Immutable Writing Lessons from Legendary Authors” along with his personal articles, essays, interviews, and book recommendations by joining his monthly newsletter.

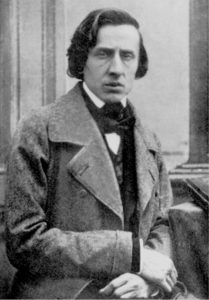

I don’t remember how or why I first got hooked on classical music. I probably thought it made me feel cultured or intelligent as an 18-year-old college freshman. Since then, though, it’s become clear that the music itself has nothing to do with making someone smart or boosting mental performance. But it has everything to do with keeping you focused, calm, and creative, of which getting shit done is usually a byproduct.

I don’t remember how or why I first got hooked on classical music. I probably thought it made me feel cultured or intelligent as an 18-year-old college freshman. Since then, though, it’s become clear that the music itself has nothing to do with making someone smart or boosting mental performance. But it has everything to do with keeping you focused, calm, and creative, of which getting shit done is usually a byproduct.

genuinely care about the material quality of goods. “Instead,” says Schor, “we’re in a world in which material goods are so important for their symbolic meaning…what they do to position us in a status system.

genuinely care about the material quality of goods. “Instead,” says Schor, “we’re in a world in which material goods are so important for their symbolic meaning…what they do to position us in a status system.

teaching a full course as a professor in addition to his own studies. By age twenty-six he was named the Dean of Students. This isn’t to say working hard as a janitor is the best path to the presidency, but Garfield’s story perfectly illustrates how a shift of mentality is the difference between feeling sorry for yourself and reaching your potential. He understood the distinction between wanting something and feeling entitled to it.

teaching a full course as a professor in addition to his own studies. By age twenty-six he was named the Dean of Students. This isn’t to say working hard as a janitor is the best path to the presidency, but Garfield’s story perfectly illustrates how a shift of mentality is the difference between feeling sorry for yourself and reaching your potential. He understood the distinction between wanting something and feeling entitled to it.

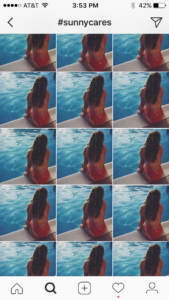

But even more interesting than girls buying overpriced ($64) pieces of fabric to cover their private parts from two bros behind a laptop in Tucson is the bold gonzo-marketing stunt that these guys unleashed today.

But even more interesting than girls buying overpriced ($64) pieces of fabric to cover their private parts from two bros behind a laptop in Tucson is the bold gonzo-marketing stunt that these guys unleashed today. Engagement with social media releases the reward-chemical dopamine – this is why getting notifications feels good. It’s why we count our “likes” and log onto social media apps when we’re bored, lonely, anxious, or depressed. When people acknowledge us, however superficial that acknowledgement is, it feels good. When someone posts “Happy birthday!” on Facebook or retweets us, a signal is sent to our brain telling us we’re relevant and desired. And the more of it we get, the more dependent the brain becomes dependent on apps for temporary relief. Soon enough it becomes an addiction.

Engagement with social media releases the reward-chemical dopamine – this is why getting notifications feels good. It’s why we count our “likes” and log onto social media apps when we’re bored, lonely, anxious, or depressed. When people acknowledge us, however superficial that acknowledgement is, it feels good. When someone posts “Happy birthday!” on Facebook or retweets us, a signal is sent to our brain telling us we’re relevant and desired. And the more of it we get, the more dependent the brain becomes dependent on apps for temporary relief. Soon enough it becomes an addiction.

will you feel about the guy who cut you off in traffic in 10 minutes? 10 months? 10 years?

will you feel about the guy who cut you off in traffic in 10 minutes? 10 months? 10 years?