Why am I distracted?

That’s usually the last question you ask yourself when a deadline is looming. With each passing minute it becomes harder to focus. So you check your email (again), you drink another coffee, you put it off until tomorrow when you’ll “have more time.”

You’ll do anything except ask yourself: Why am I distracted in the first place? In other words, you treat the symptoms, not the illness. And the illness is doing work you hate.

As children, we all had primal inclinations. We were drawn to activities that seized our attention and sparked our curiosity. We enjoyed them, not because of their perceived value, but because we developed an emotional connection to them.

We all remember spending hours on end fully immersed in our favorite activities: drawing, writing, acting, building, designing, cooking, and so on. It wasn’t hard to focus. In fact, you probably had to be dragged away to return to what you were “supposed to be doing.”

Fast forward to life as an adult. Our attention spans are shriveled. We eagerly anticipate the next smartphone notification, like rats pressing a lever for food. The TV glares in the background. Anything that offers an escape from work, even momentarily, is joyfully welcomed. We’re working for the weekend.

So, what’s the disconnect? And why does it occur?

Contrary to what some productivity gurus might pontificate about on social media, the problem isn’t a lack of work ethic or even the tiny distraction machines we carry around in our pockets. Those are cop-out answers. The problem is settling for work that isn’t engaging enough to make distractions irrelevant.

“Once you choose a career that doesn’t suit you, your desire and interest slowly wane and your work suffers for it,” says Robert Greene, author of Mastery. “You come to see pleasure and fulfillment as something that comes from outside your work.” (Emphasis mine).

Greene goes on to say that it’s our subconscious desire to conform to our parents’ expectations and social norms that pulls us away from our primal inclinations and inevitably separates us from our truest selves.

Jason Fried, the founder of Basecamp, says that distractions can serve a purpose: “They tell us that our work is not well-defined, our work is menial, or the project as a whole is useless.”

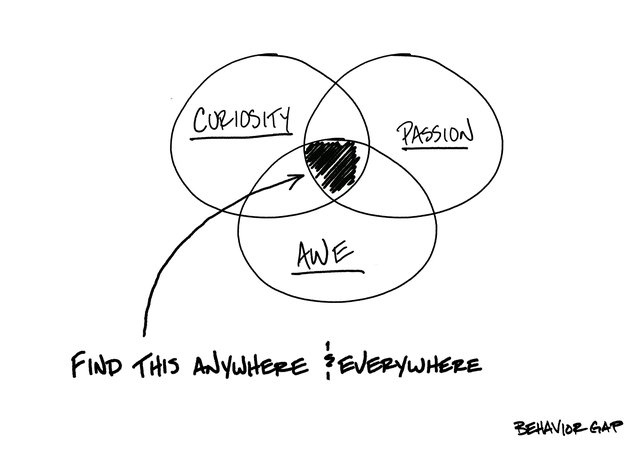

While this observation seems bleak, it offers insight into how we can conquer distractions: We have to seek out work that aligns with those primal inclinations and ignites the same curiosity we had as kids.

In order to do that, the first step must be inward. Set aside the noise and look for patterns throughout your life: What do you think about in the shower? What do you do for free? What could you talk about for hours on end? Or as Jerry Seinfeld puts it: “Find the torture you’re comfortable with.”

Whatever that is, it’s your ticket to freedom.

All masters, from Maya Angelou to Michael Jordan, followed their inner voice. They didn’t need to microdose psychedelic drugs or buy caffeine supplements. They were simply obsessed with their work.

You and I are no different in that we learn faster and work harder when we’re emotionally invested in a project. Time management expert Laura Vanderkam mentions this in her TED Talk: “Time is highly elastic. We cannot make more time, but time will stretch to accommodate what we need or want to put into it.”

There is a sense of urgency that emerges when you strive towards something you care deeply about. You forget you even have an iPhone. Psychologists refer to this as being “in the flow” – a state in which, to some degree, you become immune to distractions.

Make no mistake: every project can’t flow effortlessly from your fingertips. There will be meetings you dread. There will be grunt work. That’s part of the process.

But when you’re chronically distracted, the solution isn’t hacking your brain to get more work done. It’s taking a look in the mirror and asking whether you’re doing the right work in the first place.